- Home

- Adrian Van Young

Shadows in Summerland Page 3

Shadows in Summerland Read online

Page 3

“You think that the Reverend is silly?” said I.

“Was I that bad at covering up?”

“I think that the Reverend is silly,” said I.

“The Reverend!” said she. “Why the Reverend’s delightful. Verily, a human torch! You will have to come down to the inn,” said the girl. “My parents have taken it over, you’ve heard?”

“I hadn’t,” said I.

Which of course was a lie. Everyone in town had heard. The pretty girl from Providence whose father wore a silver fob.

“In two days’ time, I shall gladly receive you.”

Nodded and opened my mouth, but no words.

“Good!” said Grace. “We will talk and be splendid. I will take you on a tour of every mouse-hole in the house. Are you all right to walk, Miss Maier?

“Go on,” said mother. “Go. You’re kind.”

I was, for the first time, embarrassed of her while Grace wheeled around in her peach-coloured dress. A few pretty strands coming loose from her coil and riding the sea air, electric with cold.

“So nice to have met you,” she cried, walking backwards, holding her skirts above the mud.

The last time that I saw her she was standing with her parents in the nearly empty lintel of the church-house.

Q

Mother sat beside me on the carriage-ride home. Bonnet cast over her face for the light. A series of ruts and the trap started up. Tipping me suddenly into her ribs.

“All mother needs is a nice darkened room. Ain’t that the truth of it, mother?” said father. “A nice darkened room with a nice warmed-up cloth to chase off them mean winter headaches.”

Gin-fug heavy, on the wind. Father’s arm crooked as he reached in his coat. Sunday the Lord’s day but also a day when father went to sleep at five.

Up ahead another trap. Crossing the road that bisected the mountain.

“Ho, Pieter,” said father. “Get on with them nags.”

The man driving smiled and the trap cut across.

“Fleeter of foot than yours,” called Pieter.

Brood of three boys with a woman in back. A frieze of longsuffering faces theirs from all this riding in the open. And Pieter himself, who was somehow familiar. Who had, at some point, taken soup in our kitchen. Or stood with father in the hall for as long as it took them to take down a cup. But when I saw his face emerge from underneath his wide-brimmed hat, I knew him for the drowned man with the kelp in his hair that I’d seen earlier at the back of the church. Sure as Lazarus walked, here was Pieter, the drowned man, steering his carriage off into the trees.

Mumler on the Night-Side

July, 1859

By the time I arrived at the Sunderlands’ house at the chosen time of six o’clock, I have to admit I was decently tight from all I’d drunk at Fisk’s with Bill.

The day had that devil-may-careness, you see.

All of the street-facing windows were bright with lamps and guttered flames alike, the curtain faintly parted on the parlour of the house where schools of well-dressed bodies moved. It wasn’t my hostess who answered the door, but a man whom I took for her husband LaRoy—unaffiliated mesmerist, reform innovator and owner of the Banner’s sister-paper in Athens, “The Spiritual Philosopher.” Tall and stooped was this LaRoy, his golden beard made weak by white, a funnel for hearing held up at one ear.

“Why, you must be the champion of Lucretia’s afternoon,” said the man upon taking my name, over-loudly. “You needn’t have favoured her so in your pricing. But come, take a sherry. We are just circulating. Mrs. Conant’s address will commence in a tice.”

“Thank you for including me,” I told the old goat.

“Nonesuch, nonesuch,” Mr. Sunderland said. “We have daughters, you know! Well come in, sir! Come in!”

He dithered close by me while two comely maids turned me out of my coat and then into the parlour.

I grant it was strange that LaRoy Sunderland and not one of these maids met with me at the door, and yet I adduced it as part of their plan to position themselves as the salt of the earth—not moneyed Back Bay carpetbaggers but Boston progressives in every respect.

So why not start with me, I thought. Willy Mumler, who’s waited so long in the wings.

LaRoy Sunderland was a rigorous host, however hugely hard of hearing. He did his best to introduce me to the fourteen-odd assembled with the repeated combination of a facilitated handshake and ten words or less on their chief-most achievements: phrenology, literature, banking, priest-craft. The parlour was broad with strong light in its sconces, which made the sherry glasses blinding. The sherry helped to give me balance; another glass more balance still. Bespectacled faces, and faces with beards, and faces with beautiful lips, and with wrinkles, looming, retreating, extending their hands, nodding to LaRoy, their host.

Aside from LaRoy and Lucretia there were: the Sunderland daughters, Cordelia and Sarah; a man in a cello-shaped waistcoat with tails who wore dollops of rouge upon his cheeks whom I had heard from somewhere near was the modern heir apparent to the stage, Josiah Jefferson; Unitarian Reverend John M. Spear, tieless in a smoking vest and at his side a Negro boy made strange by spectacles and tweeds; a blind and reanimate mummy, F. Bly, whose specialized field was the head and its contours; a dark and dourly handsome woman with her hair gathered up in a sort of sleek harp.

LaRoy told me this woman here was the trance-speaking medium Fanny A. Conant.

Mrs. Sunderland volubly recognized me from across the packed room and came fluttering over. Along her way, she flapped her hands, as though she were chiding the air in between us.

“I see you’ve met William—our craftsman,” she said. “Isn’t he perfectly novel? Say, Reverend.”

“The very spice of life,” said Spear.

“And just the dose we need,” she said. “Did you know, Mr. Mumler, that Reverend Spear’s faith is so much confined to the loftier classes, it has a branch for normal folk that is totally identical in polity and practice?”

“Universalists,” I said.

Lucretia and Spear nodded at me, impressed.

“My point exactly,” said Lucretia. “Mr. Mumler proves my point. I wonder, John, would you have him or are his hands too rough for prayer?”

“We’d be lucky to have such a man in our ranks.”

“You sound like you’re insisting, Reverend.”

“She believes in The Spirit alone,” he addressed me. “Anything other is cause for amusement. But shouldn’t we let Mr. Mumler decide if he needs metaphysical comforts, Lucretia?”

“I am in need of a sherry,” I said.

Which elicited a garnish of sparse, polite laughter.

“I myself enjoy the privilege of parishioner, sirs,” said the young professorial Negro beside him. “And I came up from Beacon Hill.”

“Came down from Beacon Hill, dear Phineas.” Spear gave a titled, uncomfortable smile. “Came up by way of down, of course, is what the young man means to say. Yet here the fellow stands!” he said and clapped his hand upon his shoulder. “Whichever direction, we’re happy you’ve made it.”

In the barely congenial silence that followed, I made good on my proposal of another glass of sherry and, under the guise of returning said glass to a sideboard stacked with others like it, I wandered afield of John Spear and his minion to make a closer study of the Sunderlands’ house.

Here was the hall with its framed eminences, which led to yet another and another after that. A couple of liveried servants went by, bearing two towers of folded-up napkins. Removing myself from the wings of the house, I traced my way back to the parlour and past it; I passed a dressing room and washroom, and a nursery and bedroom, and from there an obliqueness of further rooms still, each one darker than the last.

I was happily and irretrievably lost.

At the end of some hall angled

off of some other, I passed a larger, lighted room that seemed to be a library. The library was very calm, a self-contained and womblike place, and voices from the cocktail party floated from the hall. Inside I was faced with the back of a man who was moving around against the window. He was busy with something, some sort of appliance, conducting it now here, now there. The appliance itself was five feet high, its bottom a juncture of three spindly legs. At the top of the legs was a sort of dark box, a shaded cyclopean eye at its centre. To the right of the man was a cloth-covered table that held an upright wooden drawer over which the man started to brood and concoct to what purpose I could not say.

I shifted in the doorway then; the busy stranger turned around.

“I do say, sir,” the stranger said, his hands held up at his lapels. “You’ve given a fellow a scare just now. I expected Miss Conant but you—have we met?”

“I expect that we haven’t. William Mumler.”

He lowered his hands and stepped back toward the window. “Taking a tour of the house, are you, sir?”

“Yes, I thought I would take one before the address but it seems that I’ve gotten myself badly lost. I’m a reader, you see.” And I swept the high shelves. “Such rooms are a sort of safe harbour for me.”

The man appeared to soften some; he gainsaid the step he had taken away.

“Algernon Child,” the man said. “Pleasure’s mine. Algernon Child of the PSAI.”

He was minutely fashioned but willowy too—no trace of stoutness in his genes—and wore above his bloodless mouth a thin and sharply trimmed moustache. And when I accepted his hand which he thrust to compensate how he was made, I found the hand met to be shockingly rough, the hand of a man who has laboured his worth since a very young age at the pick or the stylus.

“The PSAI,” I said. “A Spiritist association?”

The short man gave a little scoff. “Whatever your views on that,” he said. “No, sir, I am in photographs. Pristine, living records. The Photographic Section of the American Institute, you may have heard our name said round.”

“It’s a camera then.”

“Of the wet plate variety. You’ve yet to be immortalized?”

“Now there is a pleasure I’d like to have greatly. Though I have seen the end result.” He watched as I circled the camera up close. “You’re not a believer, why palaver here?”

“I meant no insult, Mr. Mumler.”

“You have given none, sir. My inquiry is rational.”

“An initiate, then! Oh they’ve tried, sir, they’ve tried. But I am not one to yield so gamely. And as for your question, a man’s got to eat, to pay his landlady, to frolic, you know. I am privately indentured.”

“You’re moonlighting, then?”

“I am here to take a portrait of the speaker, Fanny Conant.”

“And this?” I asked him of the table, upon which sat the upright drawer.

“A bath of silver nitrate and potassium,” he said. “To fix the negative, you see. Which reminds me—ah curses—it must be done soaking.” He rushed the table, seized the drawer. “Mr. Mumler, might I borrow your shade for a moment? Forgive me for saying, you make ample shade. Over here. Now stand just so. And shadow my path, if you will, to the slide.”

We humped our way across the room to where the prized appliance stood. Mr. Child rose on his toes to insert the glass plate in the back of the camera.

“Now the widow’s weeds,” he said, retrieving a large cloth of felt from the couch and placing it over the box with the plate. “There she stands, Mr. Mumler. The veil hanging o’er. Ready to enact her magic. I do say, sir, I’ve taken shots but for whatever reason she always beguiles me.”

“Darkness and light,” said a voice from behind us. “That, and the dependable reaction of the chemicals. Mr. Child, Mr. Mumler,” said Fanny A. Conant, appearing to glide through the library door. “I’m not very long now from being expected. Wouldn’t you rather hold off, Mr. Child?”

“Better not, Ma’am. I’ll be quick, don’t you worry.”

“Prefer that I should sit or stand?”

“Sit, Ma’am,” he said.

“Won’t the window shed light?”

“Yes, Ma’am—well, no. There’s a backdrop for that. You’re keen to every detail, Ma’am.”

“How is it that you know my name?” I asked her as she went to sit.

She fixed me with her pale blue eyes; they were housed in a long handsome face, strongly white, with a cluster of little dark moles at her hairline.

“It was because I didn’t know I asked Lucretia who you were. You’ll agree one should know every face in one’s audience.”

“And who is Mr. Mumler?” Child said, on a grin. “He’s rather a mystery to me, who just met him.”

“He’s a jeweller on Washington Street,” said Miss Conant. “Our hostess is decked in the spoils of his talent. But let us turn no soul away. So welcome, Mr. Mumler, to the new dispensation.”

Algernon exposed the plate. We were left to wait out three long minutes of stillness. This he’d explained as the optimal time for the image to make itself known on the glass.

In the portrait she is looking at the camera directly, her arms hanging shapeless and free in her lap.

Q

Fanny Conant’s address saw the clock once around, though I have little recollection of her actual words. What I do recall, at the half-hour mark, was a break in those words to admit Mr. Child, who arrived in the parlour in unnatural fluster. Moving regrettably in my direction, he attempted and failed to not crush people’s toes.

Meanwhile Fanny down in front, at a raised music stand that stood in for a podium, was somewhere in the neighbourhood of “spiritual affinities,” which she had named a precondition for the marriage of souls. The spiritual affinities, she claimed, must be realized; the spiritual affinities, she harmonized, were all. The marriage contract, else-wise, guarded legal prostitution, conceived by the husband, fulfilled by the wife.

She let her notes fall from the stand to the floor as she rapidly covered her points.

“An ultraist with uteromania,” said Algernon Child, who had fetched up beside me.

“An ultraist with what?” I said.

“An ultraist—a radical,” said Algernon, sweating. “And yet you’ll observe that she speaks out of trance. Have you seen Cora Hatch? She’s a savoury one, Cora. But never speaks outside the trance. Damp as she gets when the spirit’s upon her—”

“—do hush,” said the head-doctor, Bly, in the back.

I could see he was blind by the way that he gazed just right of the place we were actually sitting.

“Sorry, uncle, sorry,” said Algernon Child. “Keen as a bat in Brazilia he is.”

“Uteromania?” I said.

Frowning, he answered me: “Womb disease, sir. For the womb has gone tilted, you see, in the victim, leaving her defenceless to the creep of strong opinions. A most common disease among Spiritists, sir. These Coras and Kates selling ghosts by the dollar.”

“And Fannys,” I said.

“Yes, Fannys,” he said, observing Fanny Conant speechifying for a moment. “They say a third sex will be born,” he continued, “with all of this thumping of manicured hands. But looking at her—yes, looking at her.”

“I find her to be very sleek.”

“No one’s denying that,” said Child. “But Mr. Mumler, really, I saw the way you looked at her.”

“Looked at her when?”

“The library,” he whispered. “You wanted to throttle her blind when she spoke.”

“I wanted nothing of the sort. And I cannot pretend that I do not resent it.”

“Forgive me, Mr. Mumler. I’ve offended you twice.”

“Lucky for you, I am not a hard man or I should have to throttle you.” I elbowed him gently in the ribs, at which he gave a

little start. “Your profession,” I said, “is remarkable, sir. If you’re staying for dinner, I’d like to discuss it.”

“Oh look, she is finished,” said Child, striking out. “Let’s make a prospect of the dining room, sir. I could never on earth forgive myself if I ended up trapped beside F. Bly.”

Q

The “sitting” was set to take place in the parlour and, after our supper was cleared, we repaired there. I’d fallen in with Mr. Child, and we walked arm to arm, trading looks, in the herd. Others shuffled on in front, Fanny and Lucretia leading. LaRoy Sunderland went in back with his horn like some mild and oblivious prophet.

The lighting in that place had changed. I saw red shades on all the lamps. Clearly, the servants had been busy, constructing that room’s ambience. The table where we went to sit was half of the size of the one where we’d eaten, a perfect little cherry round. Upon it was a black lace cloth.

I sat flanked by Reverend Spear and of course Mr. Child the Perpetual Friend, whose palms were slick when we joined hands. We were seated intermittently women and men, with several more men in attendance. This arrangement was according to the charge of each guest, negatives and positives, women to men, so that the “telegraph of souls” could optimally transmit itself.

The rows of shaded lamps went softer. Hands were clasped the circle round. The medium Fanny began to intone toward a dim and indefinite point past her nose. A series of sharp, hollow sounds—gaunt sounds—came from somewhere underneath us. Many of the eyes were closed, but several, including my own, remained open.

Miss Conant spoke up, “We are testing the batteries.”

The gaunt sounds continued, more rapidly now. But after a while they petered out.

Then Fanny Conant began to look different. What can only be described as a physical awkwardness came over her person. Her arms grew slack, she tipped gradually forward and the hands that she held seemed to tether her there. She hung for a moment, then slowly came up. She appeared to grow out of the dark like a rose.

“Has Vashti come into the form?” she said. “Vashti of the massacre of Yellow Stone River? Oh come to us, Vashti, in paint and rawhide. Come with all your bright, black hair. Bring us tidings from your shores. Come and unveil to us beautiful truths.”

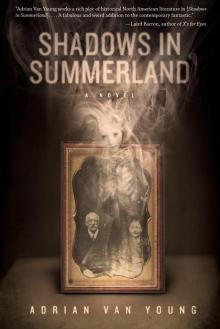

Shadows in Summerland

Shadows in Summerland