- Home

- Adrian Van Young

Shadows in Summerland Page 2

Shadows in Summerland Read online

Page 2

I got my calling cards in order.

Mrs. Sunderland seemed to emerge from the screen like some sort of fairy the way I perceived it, though really she slipped through the sliver of space between the screen’s edge and the parlour’s doorway, tailored to her size exactly. She took my card, glanced at it, scanned me lengthwise and to my surprise took my hand in her own. My hand had been swollen with heat from my pocket, yet there in the cave of her palms it contracted.

She was little and lithe in the way she was made, her hair curly as barrel liquorice. She had a pretty, cramped face just showing its lines.

She glided off beyond the screen and once I had followed her, wrenching the thing to fit my magnanimous bulk past its edge, she motioned I sit on a second low couch within her lace-curtained and cool inner sanctum. My hostess sat across from me in a brocaded wingback that bore her aloft a couple of feet above the floor. I found I was squinting because of the sun which her lady had let through the drapes as I waited, slanting over the top of her mistress’s chair and shining down into my eyes.

Set between our sets of legs was a table with coffee and small pastries on it.

“Let’s have it then, Mr. Mumler,” she said.

I took out the necklace and showed it to her in a fan on the flats of my hands.

“Would you?” she said as she rose and then I. She inclined her head foreword. “Obligingly, sir.”

Careful to maintain a suitable distance, I fastened the chain below her hair. She shook back her hair and began to process before a gleaming Cheval mirror.

“I take it you are pleased?”

“Oh, quite. And tonight I shall give it a coming-out party.”

“Special occasion?”

“A speaker,” she said. “Miss Fanny A. Conant. She’s on at the Banner of Light. Do you know her?”

“A Spiritist,” I said.

“A Spirit-ual-ist,” my host corrected. “She is to speak and hold a sitting.” Finished inspecting herself at the mirror, she sat once again in her chair. “Are you familiar with our movement?”

“As much as I’ve read in the papers,” I said.

Sitting again, I crossed my legs and tented my fingers upon my left knee. My hostess’s eyes flickered over me briefly.

“Oh we are frightfully disorganized,” the lady said quickly. “We are buffeted by skeptics almost constantly, you know. And yet we are always accepting of strays.”

“I am not wed to any faith. You see, I cannot be a stray.”

“We Spiritualists,” she said, “are more. Though I grant you that faith might have something to do with it. Are you learned, for example, on the question of woman?”

“I am learned on the answer of woman,” I said.

“Really, Mr. Mumler. What a wicked thing to say. You’re in the habit of saying such things, I imagine? And yet anyway,” she gave pause, “you’re not boring. Maybe a little passé, but not that.”

“I’ve liked our talk myself,” I said. “So much, in fact, I would like to discount you. Half-price let us say for the necklace, Lucretia?”

Her nostrils flared a little then. She did not answer for a moment.

“Oh you may call me that,” she said. “You may call me Missus L. But the size of your offer, you see—it’s indecent.”

“You are busy enough as it is,” I pressed on, “what with all your women and their questions, Mrs. Sunderland. I won’t be the cause of your falling behind all on account of some ornament.”

“We’ve been privileged enough to afford it,” she said with a curious ruffle of her dress.

This fanning of her feathers done, she smiled and moved onto the edge of her chair. And I detected in that movement an apologetic tremor or anyway one of explanation—I could not help myself, you see—as though she were now more embarrassed for me than she’d been for herself just a moment ago when I had implied that she’d needed my help.

But why, you will ask, did I wish to discount her when I was not my father and my father was not me—when I gave not a fig for Lahngworthies like Lucretia, with their frivolous neckwear and parlour revivals?

Here is the reason: I wished to deceive her.

I wished to infiltrate her graces under the pretence that I stood in worship of her. I wanted to smirk at the plush of her world, to see its frailty from inside. And I wanted, I think, to avail myself of her, to channel her relations and resources and connections towards higher, purer aims than hers.

Decisively, I raised my hand and I blocked out the sun slanting into my eyes. I said to her: “Madam, I see.”

Leaning closer toward me still, she spoke in that same vital fog of apology: “But surely there’s—oh, let me see . . .” She counted on her well-kept fingers. “Yes, surely an eleventh place can be made in our circle for one such as you. Unless you are elsewise committed?” she said.

“When you call it a sitting,” I said, leaning forward, “is it not a séance you mean, Mrs. Sunderland? Complete with planchette, levitating violins, chilly hands upon one’s shoulder?”

“The way you say it, Mr. Mumler, I should think you had decided we were charlatans already. There must exist in all of us a modicum of childlike wonder.”

“I would very much like to feel that. I will come.”

I lightly, gamely, slapped my thigh. Then appeared to go gloomy; I did a faint laugh.

“Mr. Mumler, what is it?”

I held out a moment, looking away from her briefly, then back. “Seeing I will be your guest, the price does not agree with me. Nor would it agree with my father,” I said. “Bless him that he made me, Ma’am, but my father has never been partial to bargains.”

“I can see that you will not relent,” said my hostess. “And a most welcome tyranny, dear Mr. Mumler. Half of half, all right?” She smiled. “I would gladly meet you at a quarter.”

“Do you stand firm in that?” I said.

Mrs. Sunderland frowned. “Why as firm as you stand. As you’ve stood, Mr. Mumler, against every reversal.”

Q

Which is why later on, in the hours before supper, under the guise of receiving a shipment of various gemstones arriving at Lowell, I dropped in at Fisk’s at the top of Copp’s Hill, thinking it would relax me some.

Fisk’s was—no polite way to say it—a brothel.

Last house on the right on Snowhill Street and just round the way from Copp’s Hill Cemetery, Fisk’s had been my hideaway from the day-in-day-out-ness of Mumler & Sons. There was brandy and laudanum and beer and sweet wine. Cigar smoke and opium smoke muddled oddly. There were soft, low-backed couches on which to extend while Women of Erin and Women of Ham and Celestial Women made love in your ear. I loved the ease of it. I loved its transaction.

I came there often twice a week.

Sometimes I would even pass up on the girls—Madam Fisk didn’t mind if you kept buying brandies—and sit in the shadows alone, watching others, a light tipple in me, at ease in my skin.

I would sample diversely when I had the urge (yellow Fang and black Bertha and olive Aida) though I mostly returned to the red-curtained room of a fair, Irish girl named Brianna O’Brennan.

Her name in Gaelic meant “Sad Hills.” She had told me this one night in what was verily an outpouring.

I would think of her hunched at the foot of the bed, her hair too short to hide her nipples, opening and closing her legs on her soreness, as if to hide the thing we’d done.

But she was not the only one who felt the darkened edge of something—just the faintest pollutant of sadness or shame in the wake of our nighttime and noontime encounters.

Let us call it, then, The Sadness, sharp in me from time to time.

I felt it then, and feel it now, and shall feel it, I am wholly sure, till I die. In the bedrooms of Fisk’s it would moulder in me as soon as I had spent myself, giving rise to gloomy thoug

hts that begged the point of all this searching. Not for something high-minded but pleasure itself, which seemed to me flagrant, deceitful, outrageous.

But then I would remind myself that Brianna O’Brennan was only a whore.

Which brings us back to Madam Fisk’s on the day I delivered Lucretia her necklace, aware that in only a couple of hours I would find myself deep in the enemy’s camp. I needed Brianna. I needed release. I needed somebody to pour me a drink. And with this in mind I arrived at the brothel, unfrequented in these working hours and never on afternoons past by me, so that the house Negro, a man named Bill Christian, launched from the wall he’d been leaning on smoking, thinking perhaps that I might be The Law.

“Mist’ Mumler,” he said. “Come by early today.”

“Pressing business, Bill,” I said.

“Brianna just now waking up.”

“A loyal gent at arms, is Bill.”

Bill assessed me carefully, looking to see was I drunk or unhinged. He was charged to size up every one of Fisk’s clients, whether or not they were his friends and I knew that he wasn’t above the heave-ho, if situations came to that.

Once in a gin-fog I’d seen him do violence to the face of man who’d refused to pay Madam. Bill had been smashing his face on the brick. First his nose, cocked to the side. Then his lips, rent down the middle. Then his nose stove in entire, a syphilitic pit of blood.

He was also a gorgeous male specimen, Bill—the handsomest Negro in all of the Hub. The bones and sinews of his face were overlaid with darkest satin and his plum-coloured lips were in perfect proportion. He smiled at the women and smiled at the men and he smiled at nobody at all on the street. It was Bill Christian’s armour—a pre-emptive smile, not just for white people but everyone breathing. Reaching me his flask of gin, he showed it to me now.

I drank.

“Here’s to life with both eyes open.”

“One closed and one open,” I said as I swallowed, “to throw the bastards off their guard.”

Bill opened the door and revealed me the staircase that led to the parlour crisscrossed with low couches. Standing there against the light, Bill looked like the sculpture by Charles Cordier of the Moor in the turban and Renaissance beads, and for a brief moment I felt overjoyed to be welcomed by him in this halcyon place—some sultan’s dominion, all columns and incense, giggling ladies of the veil, the prince who took a little gin and called me warmly by my name.

Off of the receiving parlour, Fisk’s became a long red hall. The place had used to have a wall that split up the floor into separate apartments but the wall had been felled and replaced with a hall that ran between the eight-some rooms. When you walked down the hallway, as I now was walking, passing by the curtained rooms, there was a sort of temple hush, a feeling of going past saints in their niches.

When I came to Brianna’s room, I saw that she was not alone. A man with skin as white as hers was mounted stride her, bombarding her groin. He had a wide constellation of moles on his back and his head was as dark as a Kilkenny mare’s. They were having their way in pantomime—plunging limbs and soundless cries. Behind her lover’s lunging shoulder Brianna’s pale face would rise up now and then, the lips retracted slightly on the dark filmy teeth and the sharp chin appearing to quiver with pleasure. Yet I detected something different in the splay of her legs, in the way that her face, every time it emerged, was fixed on a point resolutely before it, which I took to be her lover’s eyes. And oh it was a stolen sight, such that I couldn’t look away.

I fumbled myself and I clung to the curtain.

We all of us happily shuddered together, becurtained Willy Mumler and the beast with two backs.

Hannah Full of Grace

January, 1859

And then one day it happened: Grace.

Her parents kept the Shoreham Inn.

But the first house we shared was the Kingdomtide Church. Perched by North Light, at the edge of the sea.

All nave, it was, the Kingdomtide. And seemed, like its faithful, to sit there on faith. Not least for the buck and the scourge of the wind, butting at the walls year round. Nor the waves of the ocean that footed the cliffs, so high in a storm that they dashed the pine roof.

Glad to remind us, Reverend Hascall. Raised up from a boy on these raked-over shores. Salt-blooded, it was said of him, with long veins of seaweed investing his flesh. Really a reedy and stoop-shouldered man with a pale freckled face and a muzzle of whiskers.

Abner Hascall, his father, my mother’s good shepherd.

His father, her mother’s, progressing through time.

Earlier that October, the North Lighthouse had been ripped from its moorings by terrible winds. A couple of salmon dinghies had been lost along with it. Each of them packed with island men. Could not place out in the storm what part was rock and what part harbour. What remained of the boats and the men and the lighthouse were still being dredged from the base of the cliff. Already to show we were not beat, a new lighthouse was underway.

The Sunday after construction began, the Reverend Hascall assembled the flock. Those sober and not made their way to the church, where last week’s storm had made the path leading up to the building a treacherous porridge. Wallows in the places where the lighthouse cornice-stones had hammered upon the rain-slick earth.

German and English, mostly, we. Methodists, nearly to the last. The women in bonnets and dark trimless dresses. Mirthless to the very bone their charging, pale and thin-lipped faces. Sitting father to children, clan by clan.

So were they arranged today and likewise did we go among them.

Maiers walking. Maier women. My mother and I with our far swampy stares.

The first thing that our eyes perceived down the dark avenue of parishioners sitting: the Christ in perfect agony, suspended in back of the pulpit.

All this I saw, and then a stall. Families milling, children laughing. A man in the back just beside where I stood—not in the back row, but against the back wall—raised and lowered his arm in a curious gesture. Seemed to be a man alone. No family about or even near him. No reason for him to be there as he was, sinister and sad.

Brown, striped trousers. Wide-brimmed hat. A hat, at that, inside God’s house. Also, a darkness to his figure. Not a swarthiness, exactly, but a boldness or solidity. And I saw that his clothes were soaking wet, the sort of wet that never dries, the water running down his chest to pool about his untied brogues. Coming away in sticky braids every time he raised his hand, bulbs and fronds of brownish kelp. I even thought I smelled the brine.

“Ignore him, child. Go take your seat.”

But the drowned man continued to stand there, not speaking. Trickling like a statue in a garden.

“He is gone. He is no one,” said my mother. “Open up your hymnal, girl.”

“Said the two sisters of Bethany to Jesus, Oh, Lord. Lazarus our brother lies ill,” said the Reverend. “He whom you love lies ill, they said, and wiped off his feet with their hair. Answered Jesus to Mary, Martha, calmly. Slowly, so they heard his words. Said He to the sisters, Take ye heart. Lazarus’s illness leads not to death. Lazarus’s illness leads instead to God’s glory. That the true Son of God, who I am, may restore him. That I may raise—yes, raise!—him up. That he might awaken, said God, for I wish it. Sure as I stand before you now . . .”

Turned in my pew when the hymn started up and saw in a flash that the drowned man was gone. And yet I glimpsed, three rows behind, arrayed between her handsome parents, a girl my age unknown to me with a curious look on her face.

It was mirth.

Mother as stiff as a dressmaker’s doll. Listening to Revered Hascall. Or appearing to listen to him, anyway. The muscles of her face lightly tensed, then relaxed.

Tremendous coil of auburn hair. That was the first thing I noticed of Grace.

That and a small bony, rarified face. The cold of t

he church showing pink on her cheeks.

Her mother was all but the promise of her. With a bloom of dark hair and long, slender neck. The man beside her very still. Fingers meshed across his ribs. But with something of wryness in his eyes. Not smugness, exactly, but something amused, as Reverend Hascall raised his own.

“Hannah, don’t stare,” mother managed to say.

Already we had this in common: aloneness. Letting the curse fall where it may.

“Hannah, go see to your mother,” said father as we filed down the aisle once the service had ended.

Mother’s brow gone reflective with sweat. Her lips dry.

Grace’s first words: “Is your mother all right?”

My eyes went darting, panicky. As though the voice were in my head. Then I saw that the girl had detached from her parents, was suddenly standing in my path.

“Just a little faint,” said I.

“Some calomel, then,” said Grace. “For the purges. A fair warning, though: it will dry out the eyes.”

Mother leaned against a pew-back, half aware of where she was. Father ahead, looking back in vexation, eager to smoke in the cold with his friends.

“We shall help her together, all right?” said Grace. “Here, Ma’am.” Alongside her. “Now cling to my arm.”

Said mother: “You’re kind.” And accepted the arm. Accepted with a rigid smile.

“I’m Grace,” said Grace. “Now tell me yours.”

Said I: “I am Hannah Maier.”

“You have immensely kind eyes, Hannah Maier. Are you kind?”

“I would like to think so, miss.”

“Don’t call me miss. Say Grace,” said she. “Say Grace”—the girl laughed—“as you do at your table.”

“Grace then,” said I, leading mother along. Continued out into the muck of the churchyard.

Father in a pack of men. Rocking on his cork-soled shoes. Lot of them smoking wordlessly with the grotty intentness of gamblers.

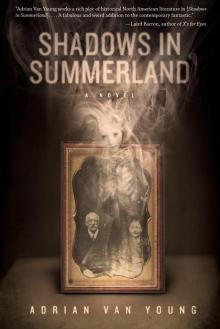

Shadows in Summerland

Shadows in Summerland