- Home

- Adrian Van Young

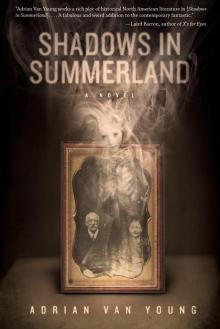

Shadows in Summerland

Shadows in Summerland Read online

Praise for Adrian Van Young

“Shadows in Summerland is an extraordinary novel certain to enchant readers of Sarah Waters as well as those looking for a thrilling and transporting gothic tale rich in atmosphere and unforgettable characters, dead and alive. Like the novel’s illusive daguerreotype photographs, author Adrian Van Young captures the limitless wonder and dark mysticism of the 19th century with incredibly authentic detail, so readers are borne into a chilling and otherworldly gothic landscape. Shadows in Summerland is sure to keep readers awake until the witching hour, in the company of an unforgettable cast of characters—spiritualists, photographers and their mercury vapors, a couple on trial for their lives, a girl who sees ghosts, and the enchanting ghost themselves.”

—Julia Fierro, author of Cutting Teeth

“Fans of Adrian Van Young’s Gothic short stories will find a lot to admire in his debut novel, a horror-filled historical riff on 19th-century séances, spirit photography, and mediumism. William Mumler emerges here as a memorably monstrous entrepreneur, exploiting the living and the dead alike, and moving with equal ease among drawing rooms, darkrooms, and freshly dug graves. In charting his social striving in a milieu of Bostonian clairvoyants and con artists, Van Young has produced a witty and disturbing horror novel: it’s as if Henry James had written an issue of Tales From the Crypt.”

—Bennett Sims, author of A Questionable Shape

“Adrian Van Young is the secret love-child of so many authors I admire, from Ambrose Bierce to H.P. Lovecraft to Sherwood Anderson to Tobias Wolff. The stories in this collection are not easily forgotten.”

—John Wray, author of Lowboy and The Lost Time Accidents

“Adrian Van Young channels such a diversity of mighty literary voices, you’d think this book was an anthology collecting the work of the best young writers of the new generation. But in truth all these stories were written by one man: an astoundingly talented writer.”

—Ben Marcus, author of The Flame Alphabet and Leaving the Sea

FIRST EDITION

Shadows in Summerland © 2016 by Adrian Van Young

Cover artwork © 2016 by Erik Mohr

Cover and interior design © 2016 by Samantha Beiko

All Rights Reserved.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Distributed in Canada by

Publishers Group Canada

76 Stafford Street, Unit 300

Toronto, Ontario, M6J 2S1

Toll Free: 800-747-8147

e-mail: [email protected]

Distributed in the U.S. by

Consortium Book Sales & Distribution

34 Thirteenth Avenue, NE, Suite 101

Minneapolis, MN 55413

Phone: (612) 746-2600

e-mail: [email protected]

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Van Young, Adrian, author

Shadows in Summerland / Adrian Van Young.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77148-383-4 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-77148-384-1 (pdf)

I. Title.

PS3622.A45S53 2016 813’.6 C2016-900934-3

C2016-900935-1

CHIZINE PUBLICATIONS

Toronto, Canada

www.chizinepub.com

[email protected]

Edited by Sandra Kasturi

Proofread by Tove Nielsen

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts which last year invested $20.1 million in writing and publishing throughout Canada.

Published with the generous assistance of the Ontario Arts Council.

for my parents and Darcy, as ever

The more intently the ghosts gazed, the less

Could they distinguish whose features were;

The Devil himself seem’d puzzled even to guess;

They varied like a dream—now here, now there;

And several people swore from out the press,

They knew him perfectly; and one could swear

He was his father; upon which another

Was sure he was his mother’s cousin’s brother:

Another, that he was a duke, or knight,

An orator, a lawyer, or a priest,

A nabob, a man-midwife; but the wight

Mysterious changed his countenance at least

As oft as they their minds; though in full sight

He stood, the puzzle was only increased;

The man was a phantasmagoria in

Himself—he was so volatile and thin.

—Lord Byron, The Phantasmagoria

Mumler’s face is one of the few from which one fails to gather any trace of character. It is calm and fathomless, and although it would be harsh to say that it is unprepossessing, it is yet a face which one would scarcely be able to believe in at first sight.

—The New York Daily Tribute, 1869

Mumler in the Dock

October, 1861

I sit here before you unjustly accused. I sit here at your mercy, reader.

We three sit before you, a congress of rogues, and all our fates are intertwined.

There is I, William Mumler, the spirit photographer. There is Hannah, my wife, who can reckon the dead. There is William Guay, our Poughkeepsian friend, who has up to this juncture protected our interests. And these are just the tattered souls who sit here left and right of me in the Year of Our Spirit 1861, bearing credible witness, in Suffolk Court’s dock.

Publically we are accused of fraud and larceny most foul.

Privately we are accused of a murder that cannot be publically proven on account of the fact that the man it concerns cannot be verified as dead.

Put forward uniquely, such charges might crush us. Taken together, they cancel each other.

For now we sit here in our cells—mute, incoordinate, fearing the worst. The jail is a piece of well-meant legislature, the new human way to prohibit and punish—four long wings of Quincy granite branching from an octagon with enormous arched windows admitting Charles Street where people, in their freedom, go. Not so William Mumler, confined behind bars, impotent and indisposed, his head inclined into a storm of rapists, pickpockets, cardsharps and abusers in a ten by four space where the sunlight itself, shining raggedly into the arms of the cross, has not the slightest character, the slightest touch of heaven in it. While forever the knocking of implements, scratching, the grunting of a hundred apes, those sad and headstrong bouts of sound that men fallen into the sere will enact.

And though I am not one of them, I am neither, however, completely not guilty.

But I didn’t bamboozle American mourners, and I didn’t murder the man that they say.

It is these crimes and these alone for which I am brought here to answer today.

Message Department

What moves our tongues to speak your names, you mortals who tend on the ways of the spirits? Why do we shiver if not to feel cold and why lament if not bereaved? Why do we wander if not to discover and why watch over if not to guard? And would you believe us, you passers among us who cannot hear our ceaseless pleas, that we shiver and sadden and wander and watch because we cannot help but do? And would it pain you in your beds, in which you sleep to wake again, that all of these and more but stir the same collective nerve of us, a network of spirits, each bound to the next—each spirit a story,

each story an absence, each absence a loss in the world, a bleak room, a beggar’s shack we pace amidst? So what do we say to you? What do we say, you mortals, you breathers, you feelers, you babes? What do we say to all of you to whom at last the answer matters?

Hannah at Clayhead

August, 1845

Born half-dead, so I’ve been told. Not a single tearless cry. Pulled me out backwards, strangling on my mother. Then lifted me into the light for a breath.

Took one in. So here I am.

Ghastly and purple: some flower in ruin. Or a big withered beet. Or a corpse flower: yes. Passed down to my mother who held me aloft to the various shades in the room.

Little girls forget, see nothing. This was not the case with me. For here is my mother, a young woman then. Middle of her dress undone. One of her breasts spilling out of the gap to let down milk between my lips. Resting over her sternum, a cameo portrait that held a face not unlike hers. In careful inks. With charcoal depth. The Maier flute below the nose. The hard flattened cheekbones. The widely spaced eyes.

And here is my father in pouting grey clothes. Muttering a benediction. Petting me along my sides. Always reeking of fish, not enough, far too many. The inherited curse of grey fish, caught in nets, resting pickled and smoked on others’ tables.

There was tribulation living in his lungs, even then. Starting, already, to tatter him.

Nights the ocean smote our island. Hurtling against the rocks. Our house stood at Clayhead, a perilous clime. Where before your every step, above the mottle of the rock-beds, you could fairly hear the snapping of your bones as you fell. The year after I came, a lighthouse went up. So many salmoners lost to the waves. Unluckier families than me and my own accepting cold bratwurst and strudel.

Q

Saw others, too. Not the salmoners. Others. Earlier, even, than anyone guessed.

They made a very queer parade through those first couple of years of my life in the vale.

Stupid and stubborn. Confused in their movement. Lummox shadows trundling by. Asked me of things about which I knew nothing. Never seemed to look at me for long, or directly. Stood in dark rooms, turned into the corner. Distractedly perched on the edge of the bed. Walked up to doors where they paused for a moment, unsure of the thing that they sought. Turned around.

But I was not the only one. Mother saw them, too.

Claudette.

Gaunt as a birch. Undappled grey eyes. Tight about the thin, chapped mouth. High-collared dresses all the colours of a rainstorm. Hair long and dark as a river at night. Corded wood the same as father. Levered our trap from the deep April ruts. Hoisted great cauldrons of stew from the fire without a bit of broth the lesser. They said when Claudette pushed me out, she lowered her legs, very still, from the stirrups and rested her feet on the floor. When she sat on a chair in her kitchen dominion and carved her figures out of soap, I felt that nothing could displace the bucket wedged between her knees. These figures she kept in a drawer in her bedroom. Latch was always snug in place. Yet still I sensed the dolls sometimes. Seeing my way through her room with their eye-nubs.

Nights my mother sang to me. A song without rhythm. Yet music it was. Said that it came from the Bible, my mother. Her Bible and hers alone.

“Your hair is like a flock of goats, moving down the slopes of Gilead. Your teeth are like a flock of ewes and every one bears each its twin.”

Tapping with her fingers on the surface of my teeth, she would kiss my forehead and would let her lips linger. Would kiss me and brush back the goats in my hair. Spilling them, scrabbling, down onto my shoulders. While just outside the ocean waves dashed and murmured on the rocks. Light from the lighthouse, magnesium, molten, cutting back and forth above us. Flickering into the room’s darkest corners. Darting again out to sea.

Q

Who came first.

The governess. Out wandering among the dunes.

Me there with my mother, the two of us watching, as the girl in the Grecian-bend bustle came on. My mother stood facing away from the sea. A tepid winter sun behind her. Yet the light was enough to determine her shadow, which stretched, twice her height, inland from the cliff. The figure approached us not head-on, but rather instead from an easterly tack. Coming up over the waist-high dunes between Clayhead and the ocean. Hair half piled upon her head, half straggling about her shoulders. Nostrils raw. Skin pale to translucence. Bright, blue veins reaching under her scalp. But as she approached, drawing closer and closer, I found I could only see her less. Perspective of her shifting clockwise unless I stood completely still.

Mother was without this problem. She followed the girl steadily with her eyes. And pivoted where she stood, my mother, to match the figure’s every motion. Matched them, and ticked like a sundial behind them, as though to keep the figure within range.

“Where are my children? Lavinia? Miss Pearl?” said the girl into her cold, cupped hands.

“And where is my stick for biting on?

“Where is the Doctor and where are his salts?

“Why am I dizzy so close to the sea when precisely sea-air was prescribed me?”

And my mother replied, “Go home to God. You are long overdue at His side, darling girl.”

“Is that where they have gone—to God?”

“So will we all one day,” said mother.

A pause from the her. A thoughtful pause. A human pause, it seemed, at first, and I remember thinking: I can really know them, can’t I? Know them like my flesh and blood.

“Did falling sickness land me here?”

“Like as not, it was,” said mother.

“Then where’s my stick for biting, miss? Don’t you know I’ll be needing it soon?” said the girl.

Standing there pinching the tulle of her dress. Waiting for the fit to come. And then when it didn’t she muttered away. And that was the last time I saw her.

Mother knelt down, drew a sharp arm around me. “You’re looking at them wrong,” said she.

I was then four. Said I, “How’s that?”

“You’re trying to trick yourself into seeing them.”

“They squirm a lot.”

“It’s these that squirm.” Mother pointed at her eyes. “Let them do the work they’ll do. Learn to trust in what you’ve got.”

“What’s that?” said I.

“The ken.”

“The ken?”

“The ken,” said my mother, but said nothing more.

Mumler on Dress

To the true gentleman, it should go without saying that his physical appearance is an index of his character. His mode of dress concurrent with the rigour of his hygiene and the neatness of his grooming are pre-eminently vital. The American gentleman is no different, and so is honour-bound to be that which his country boasts of him. Sober, strong, self-governing, with nary a hint of anything that beggars immodest regard from his fellows: the foppish or brigandly wearing of jewellery, the compassing of one’s top-hat with bands of sealskin, silk or satin, the adoption of a formal coat that finds the wearer out-of-season, and so the wrongs accumulate until the scoundrel is consumed. But in the American gentleman, lo, such conflagration need not rage. This prodigy of taste and tact should refrain from not only arraying his wealth if he is blessed enough to have it but moreover still from discussing its prospects or making it known in any way. In mind as in make as in manner, this man, and never the tierce, in him, shall cleave. He should be neat in the extreme—his moustache trimmed, his frock-coat smart—inviting no further impression whatever than that, precisely, which he is: a gentleman about his business, a gentleman to be admired.

Mumler on the Up and Up

July, 1859

In the summer of 1859 with all of life’s prospects assembled before me, I was sent to deliver a cameo necklace to the Sunderlands of Exeter Street in Back Bay.

The necklace was silve

r and dripping with cameos after the Egyptian fashion, with forget-me-nots cut into the mounting and four amethysts ranged around.

In the jewellery shop where I worked with my father off Newspaper Row in the heart of downtown, I had a name for all of them who came peacocking through the door. I would whisper it, seethingly, under my breath no sooner had the door swung closed—a door that bore upon its glass the words Mumler & Sons, my unthinkable future—coming and going, and going and coming, I would utter my withering secret aloud: “Lahngworthies, Lahngworthies, every last one.” I would murder the A as they did on Cape Cod, these Spiritists and womanists and anti-Sabba-whatsit-nists, Boston Brahmins each and all, these people who bought jewellery to gussy up their worthless lives. They wrought nothing, did nothing, squandered the triumph of having more than most—than me. They were contemptible in that.

And yet I kept an open mind.

I, William Jr., was the shop’s chief engraver, not because of my father but rather my hands, quick and exacting for all they were stubby, sweeter than a barren maid to the baubles and chains that came under their care. When I came down the stairs from the modest apartment that my father allowed me above the workshop, the other craftsmen on the floor would turn their eyes in shame from me.

Such was my estate on that red-letter day in June of 1859 as I walked down the Green in between the house-fronts past the old and tyrannical names of the street-signs.

Moving west there was Berkeley, Clarendon, Dartmouth, until Exeter came like the edge of a cliff; I stood, nervous despite myself, in front of a puddingstone sliver of house that matched the address on the ticket.

I checked on the state of the cargo I carried and went up to knock on the door.

A servant girl answered, took my name and led me to sit in the carpeted foyer on a couch with a hideous pattern of tulips directly across from a grandfather clock. Though I was early at the house by no more than a couple of minutes, still I must wait for those scrupulous hands to light on the hour I was set to arrive. Beyond a sort of canted screen between the parlour and the foyer I saw a figure in rotation, Mrs. Lucretia or her lady, preparing the room for my coming.

Shadows in Summerland

Shadows in Summerland